“THE POLICY OR ACTION OF USING VIGOROUS CAMPAIGNING TO BRING ABOUT POLITICAL OR SOCIAL CHANGE.” (Definition from Oxford Languages)

OTTAWA HYPERREAL PAINTER AND RETIRED PSYCHOTHERAPIST SHERYL LUXENBURG SAYS THAT TIME IS UP TO SPEAK OUT ABOUT A CRIME OF OPPORTUNITY

FROM PAIN TO PAINT

A 5 minute read

I was born and raised in Montreal, Quebec and moved to Ottawa, Ontario after receiving two graduate degrees in clinical psychology at McGill University and The University of Ottawa. I spent two decades working as a clinical psychotherapist and specialized in family systems and trauma. I also worked as an expert witness in trauma and sexual abuse cases in the Ottawa court system.

After being diagnosed with Collagen Vascular Disease, namely Systemic Lupus in the late 1990s, I decided to leave the profession. In the previous decades I had always explored my passion for painting. Throughout my childhood and well into the mid 1980s, I received fine art training at Concordia University, Keene State College and The Banff Centre For The Arts, but decided to pursue a clinical psychology career rather than fine art as a more stable way to generate an income. After I retired from being a psychotherapist some 24 years ago, I decided to paint full time.

Through the years my subject matter has combined a lifelong interest in clinical psychology with a passion for fine art. More specifically, my work has revolved around people or objects that experience some type of distress, such as confusion, dread, conflict, anger or numbness. Emotions related to feeling overwhelmed, useless or abandoned have also played prominent roles within my compositions. I had an epiphany 20 years ago when I realized that my subject matter was a direct projection of the psychological struggles I was having in my life.

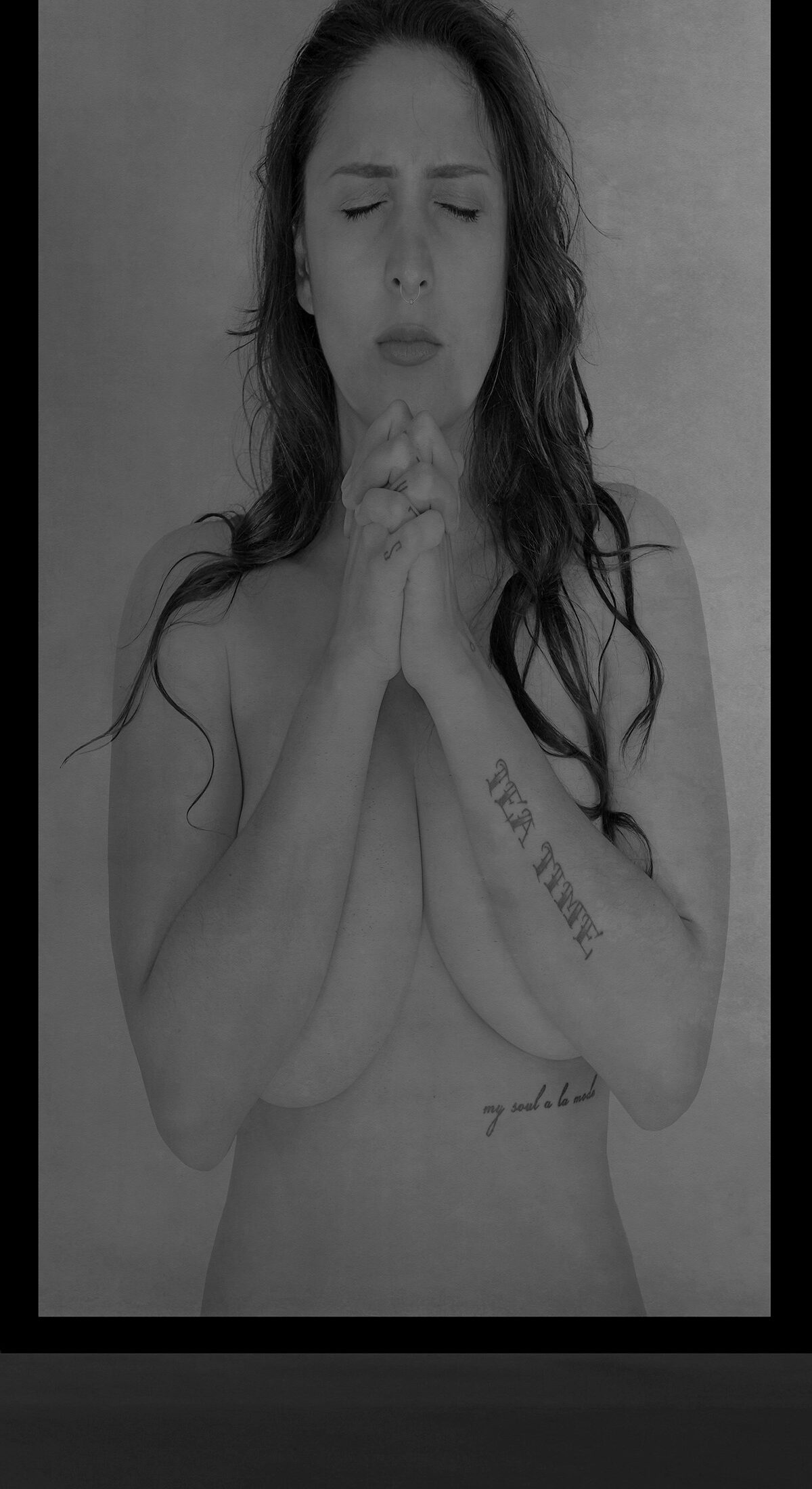

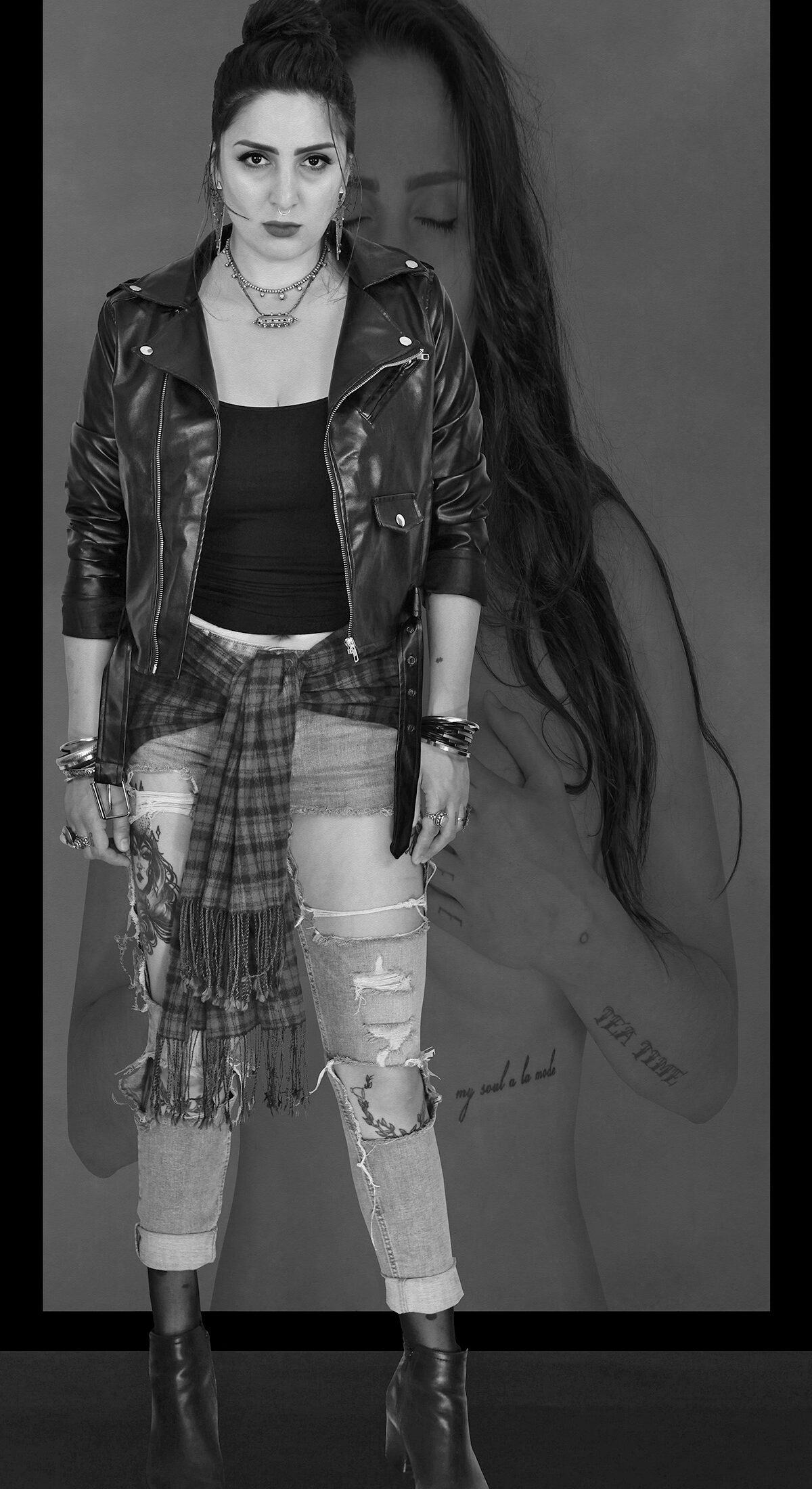

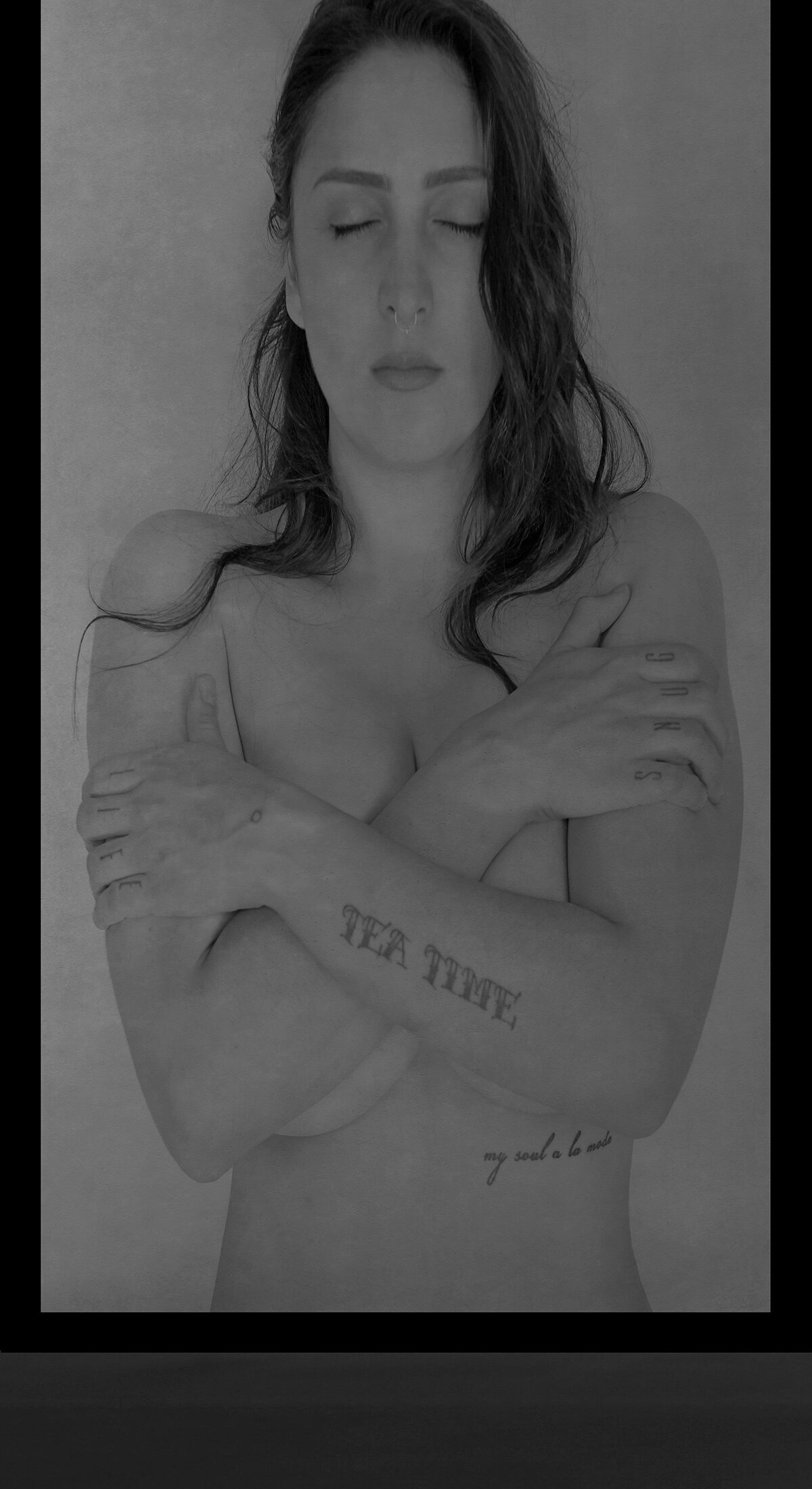

To celebrate an approaching milestone birthday in 2018, I designed and began painting a triptych called ‘To Everything There Is A Season’. Each panel is 3x6ft and I used acrylic paint with charcoal on linen canvas. The subject is about survival, transformational growth, recover and healing. Most importantly I want to use the painting to raise awareness for the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements because I am a sexual incest survivor and have never spoken publicly about this before.

The painting shows three topless figures on a cement wall which represents the past. The arm gestures are clearly communicating ‘Do not touch my breasts!’, while the central figure standing life size represents survival.

I came from a highly unstable home. My parents married young, my mother age 19 and father age 23. They were unhappy from the beginning of their marriage. My mother emotionally left the marriage early on as she would leave the house every night. This left me home with my father who for as long as I can remember sexually abused me in the form of trying to touch my breasts. This type of incest was all I ever knew, and being born into it I never knew it was wrong, even though it felt extremely uncomfortable. I was born in 1954 and no one ever spoke of such things. There were no Canadian laws protecting children from such abuse until 1988, when changes to the Canadian Criminal Code and the Canada Evidence Act specified what constitutes child sexual abuse offences. These new laws expanded the opportunity for courts to receive children’s testimony.

My parents finally divorced when I was 13 years old and the abuse intensified during weekly custodial visits. In fact the abuse continued until I was well into my 30s, married and with a child. As the years passed, the secrecy I was carrying felt hypocritical because as a professional mental health practitioner, I was trained in the mandatory reporting abuse to the authorities and would do so when the occasion would arise in the course of my professional duties.

For not one moment in my life have I ever doubted that my father loved me, but I also and more importantly have had to acknowledge that he horribly exploited his position of power as a parent. I never confronted him during his lifetime and he passed away in 2015.

I was brought up and groomed to feel sorry for my father. I tried to remain strong and ambitious to carry on with my life. I had friends and did well in school. I distinctly remember never wanting to return home and would stay for entire weekends in the home of my best friend. I remember feeling physically self conscious, but never knew why. In fact I didn’t realize how psychologically damaged I was until decades later in the late 1990s. My father always acted as if he genuinely loved me, but as my parent’s marriage fell apart, I became his confidante. Understandably my father was devastated by my mother’s rejection and he was lonely. As I grew to be an older teen and young adult, I became aware that this grooming was a distraction from the fact that he was objectifying my body for his pleasure. With the help and support of my husband, safe people, my psychology training, a few decades of distance away from my father, and psychotherapy, I have worked hard to find the freedom from the confusion and entanglement of this highly upsetting situation.

Given my clinical psychology education in the 1970s, I was trained to use DSM which is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, a classification system of officially recognized disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association. This manual is used by all mental health professionals to ensure uniformity of diagnosis. As I became well educated about personality structure, emotional functioning and anxiety disorders, I came to realize that my father had been suffering from a mental health condition revolving around a generalized anxiety disorder and a cluster of behavioural disorders associated with the impulse disorders, namely Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder. This new-found knowledge provided a greater understanding into my father’s psychopathology, but I must confirm that no amount of compassion will ever exonerate him from his criminal wrongdoings. To this day I have to live with the fact that he had been committing an indictable offence for all those decades and it went unreported.

In 2002 I chose to tell a few family members and close friends about the abuse. I received loving support from everyone, but have never gone public until now. My attitude changed when I learned about the American #MeToo and #Time’s Up movements. The victim, the psychotherapist and the artist in me began to realize that if I was to support and encourage all sexual abuse victims to speak up, I would need to use my voice and my art to share my story.

I am writing this today in the hopes that anyone who reads this article, has had a similar experience and has never spoken up, will have the courage to do so. Please speak up, tell someone and receive professional help if you need to.